The Original Black Chamber

The United States entered the Great War in 1918 with an intercept service of limited experience, and with equally limited experience in making and breaking codes. In the course of the war, the U.S. Army developed a cryptologic service that was probably the equal of any in the world.

And then the Army demobilized it.

At the conclusion of World War I, the U.S. Army had to adjust to steep budget reductions as Washington tried to return the government to pre-war levels of activity. Many programs important to modern warfare were downsized or eliminated. The "listening in" service, which had been important to the conduct of operations in France and to saving American lives, was one of these.

Conversely, however, as the military eliminated this function, the civilian side of the government established an organization to do it. This was the first peace-time national-level intelligence agency in U.S. history. Tellingly, it was a code-breaking organization.

The sponsor for this organization was the State Department, although the Army and the Navy shared in the budgeting and decrypts. Herbert Yardley, formerly a code clerk for the Department of State, recently a major in command of MI-8, Military Intelligence's wartime cryptologic section, was chosen as head of the new civilian organization.

Yardley was and is a fascinating character. He had a reputation as a blatant self-promoter and a "wheeler-dealer" in business. He was a dedicated poker player and, by his own admission, a womanizer. He was also a skilled and serious practitioner of codebreaking.

Yardley's proficiency as a telegrapher brought him from the small town of Worthington, Indiana to Washington, D.C. His steady job as a code clerk in the Department of State enabled him to send for his hometown sweetheart, and they were married in the District of Columbia. He was employed by the State Department from 1912 until he entered the military in 1917.

The regular duty of a code clerk at Yardley's level was simply to register incoming cables from U.S. diplomatic posts overseas and distribute them to the correct pigeon-hole. Ever restless, and bored on the night shift, Yardley took notice of incoming messages in cipher and began to wonder whether the crypto systems really protected American secrets. To keep himself amused, he attempted to solve State Department cables, and quickly learned that American secrets were not safe.

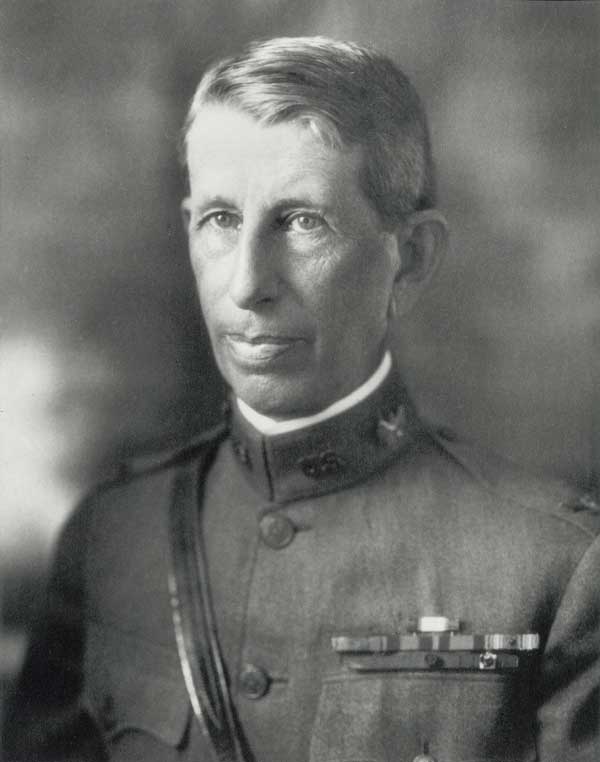

Through reading and further experimentation, Yardley became proficient at cryptanalysis, though hardly an expert. Yet, when the United States entered World War I, he met with Major Ralph Van Deman, the head of Military Intelligence, and emerged as chief of MI-8, the code section.

Yardley spent the war in Washington, starting out in an office on the mezzanine of what is now Theodore Roosevelt Hall on Fort McNair. Toward the end of the war he was sent to Europe to meet with Allied cryptologists, but little came of these meetings. He emerged from the war with the rank of major.

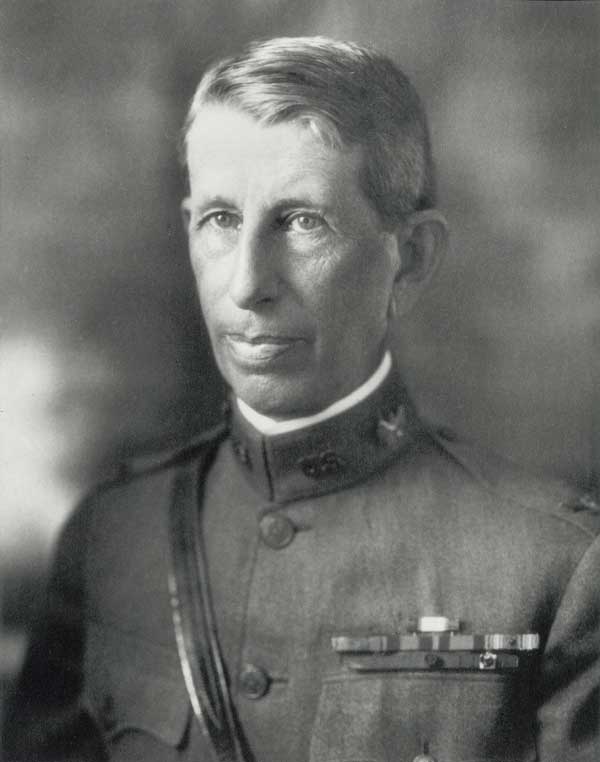

Major Ralph Van Deman

Although the military demobilized its COMINT units after the war, the civilian side of the U.S. government began to appreciate the potentials of Communications Intelligence.

An agreement between the Acting Secretary of State and the Secretary of War in May 1919 created the Cipher Bureau. The original concept called for a $100,000 annual appropriation, with the Army providing 60 percent. However, since the Cipher Bureau concentrated on diplomatic decrypts, which were of lesser interest to the Army, the Chief of Staff cut the Army's contribution and left funding of the Bureau primarily with the State Department.

Based on his leadership during and immediately after the war, Yardley was selected as chief of this unprecedented organization. He assembled a staff and began operations - in New York City!

There were a number of sound bureaucratic reasons for locating the Cipher Bureau outside Washington, not least of which was the location in New York of several cable companies with international connections. America's first civilian intelligence agency began work in the Big Apple disguised as a company that compiled commercial codes for banks and businesses.

Yardley later claimed that the Cipher Bureau solved the systems of two dozen foreign countries. Many of the records of the organization no longer exist, so it is impossible to verify all his claims. However, it is known that he provided valuable information from Mexican communications about on the revolution south of the border.

The Cipher Bureau is best known for its work during the Washington Conference of 1921-22 and the resultant Five-Power Naval Treaty. This gathering was an attempt to limit the size of postwar navies and thus head off an international arms race.

During the conference, Yardley himself, with assistance from his staff, solved the cipher used by the Japanese representatives to this conference.

The decrypt intelligence produced by the Cipher Bureau during the Washington Conference was of mixed importance. Some was timely and revealed the Japanese government's internal discussions (and dissents) over its negotiating position for the conference. Some of the Bureau's translations were late and covered information already revealed in the press - but even these decrypts had value, since they confirmed or refuted media reports that were of unknown validity.

The Washington Treaty imposed a limit on capital ship tonnage by the major powers. Yardley's decrypts helped the U.S. negotiators encourage Japan to accept its minimum position rather than hold out for a higher tonnage level.

Yardley later claimed that the Cipher Bureau solved the systems of two dozen foreign countries. Many of the records of the organization no longer exist, so it is impossible to verify all his claims. However, it is known that he provided valuable information from Mexican communications about on the revolution south of the border.

The Cipher Bureau is best known for its work during the Washington Conference of 1921-22 and the resultant Five-Power Naval Treaty. This gathering was an attempt to limit the size of postwar navies and thus head off an international arms race.

During the conference, Yardley himself, with assistance from his staff, solved the cipher used by the Japanese representatives to this conference.

The decrypt intelligence produced by the Cipher Bureau during the Washington Conference was of mixed importance. Some was timely and revealed the Japanese government's internal discussions (and dissents) over its negotiating position for the conference. Some of the Bureau's translations were late and covered information already revealed in the press - but even these decrypts had value, since they confirmed or refuted media reports that were of unknown validity.

The Washington Treaty imposed a limit on capital ship tonnage by the major powers. Yardley's decrypts helped the U.S. negotiators encourage Japan to accept its minimum position rather than hold out for a higher tonnage level.

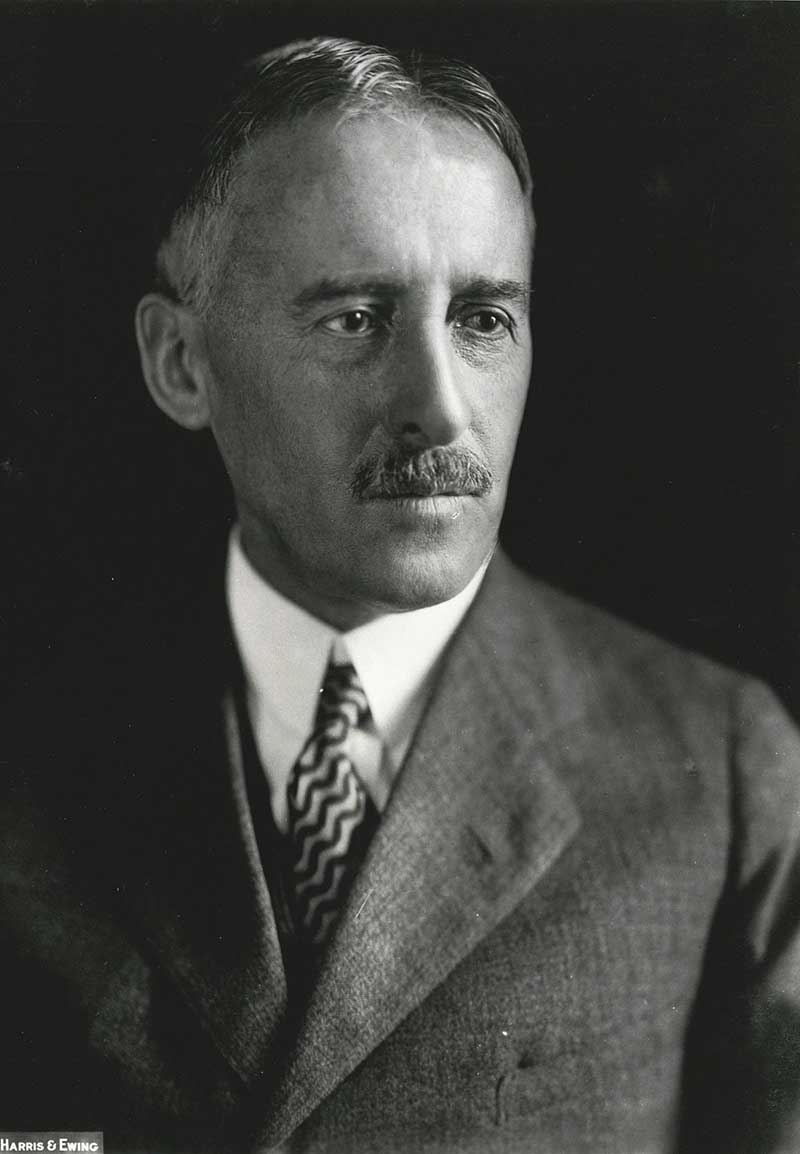

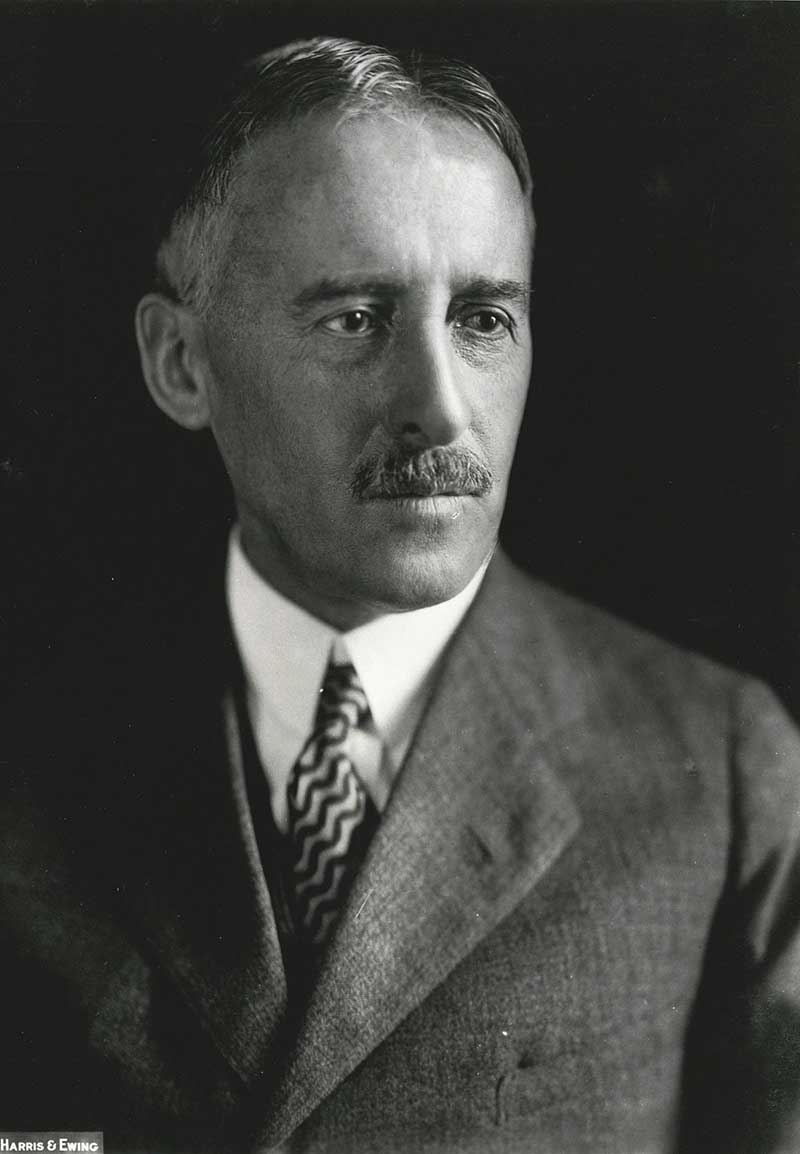

The election of 1928 brought Herbert Hoover to the presidency, with Henry Stimson as his Secretary of State. Stimson was one of the towering figures in foreign and defense policy in the first half of the Twentieth Century (he also later served in Franklin Roosevelt's administration as Secretary of War).

Stimson made a decision to eliminate the Cipher Bureau. The decision likely was based on budget considerations, but it has come down to us as based on the need for acting in good faith in international relations. Whatever the reason for terminating the Cipher Bureau, when he did so Stimson spoke the single most famous sentence ever uttered about codes and ciphers: "Gentlemen do not read other gentlemen's mail."

"Gentlemen do not read other gentlemen's mail"

In his history of the Cipher Bureau, Yardley charged that Stimson had axed the organization strictly for moralistic reasons. In his own autobiography, Stimson did not deny this: he noted that although he became a heavy consumer of decrypt intelligence in wartime, certain practices that might be necessary during war were unacceptable during peace.

One other important factor apart in the decision to dissolve the Cipher Bureau was the reorganization of the Army's cryptologic units. In May 1929, the Signal Corps assumed responsibility for cryptology from Military Intelligence and wished to rebuild it from the bottom up to serve military needs better. A half-hearted offer was made to Yardley to join a new cryptologic organization, but at a salary the Signal Corps expected he would refuse.

The upshot: in late 1929, employees of the Cipher Bureau were given three months' salary as severance pay, and dismissed. They had been employed using "confidential funds," therefore had no civil service status or rehire rights.

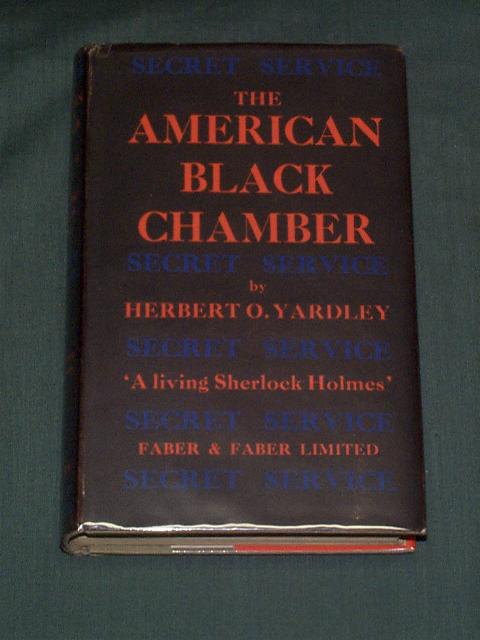

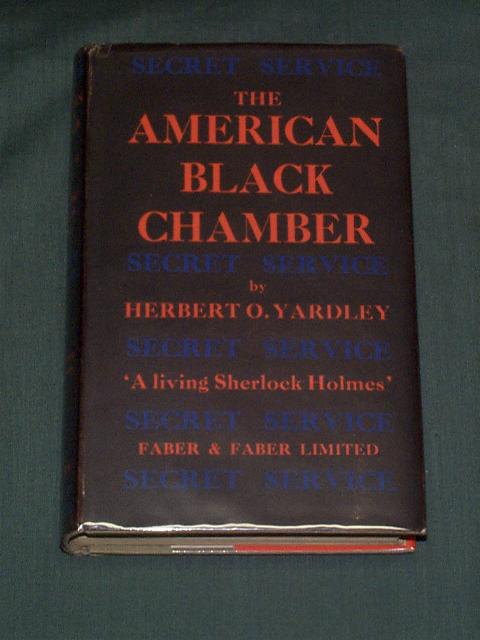

Out of work, with a family to support, and few prospects as the Great Depression worsened, Yardley decided to write his story. It appeared first in serial form in The Saturday Evening Post, then as a book, The American Black Chamber.

The American Black Chamber was filled with good stories well told, as well as frank descriptions of Yardley's successes in cryptanalysis. It was a best-seller in 1932 -- overseas as well as domestically.

While many of his former colleagues and those now engaged in military cryptanalysis were appalled at the revelations in his book, Yardley defended his publication. He claimed self-righteously that his only motive had been to alert the United States to the weakness of its own systems and to the power of cryptanalysts. What he could do, he said, people in other nations could also do.

The American Black Chamber

It has been difficult until recently to assess the contribution of the Cipher Bureau to policy. For most cases, the only account of its activities were Yardley's own. With the exception of the Washington Naval Conference, it is impossible to state unambiguously that Yardley's operation directly affected policy formation or the outcome of negotiations.

But, if it did not provide continuity in U.S. cryptologic service, the Cipher Bureau at least had the distinction of being the first national, civilian intelligence organization in peacetime. Yardley and his staff gave the U.S. government what it had never had before, and what it would soon acquire an insatiable appetite for.

The Original Black Chamber

The United States entered the Great War in 1918 with an intercept service of limited experience, and with equally limited experience in making and breaking codes. In the course of the war, the U.S. Army developed a cryptologic service that was probably the equal of any in the world.

And then the Army demobilized it.

At the conclusion of World War I, the U.S. Army had to adjust to steep budget reductions as Washington tried to return the government to pre-war levels of activity. Many programs important to modern warfare were downsized or eliminated. The "listening in" service, which had been important to the conduct of operations in France and to saving American lives, was one of these.

Conversely, however, as the military eliminated this function, the civilian side of the government established an organization to do it. This was the first peace-time national-level intelligence agency in U.S. history. Tellingly, it was a code-breaking organization.

The sponsor for this organization was the State Department, although the Army and the Navy shared in the budgeting and decrypts. Herbert Yardley, formerly a code clerk for the Department of State, recently a major in command of MI-8, Military Intelligence's wartime cryptologic section, was chosen as head of the new civilian organization.

Yardley was and is a fascinating character. He had a reputation as a blatant self-promoter and a "wheeler-dealer" in business. He was a dedicated poker player and, by his own admission, a womanizer. He was also a skilled and serious practitioner of codebreaking.

Yardley's proficiency as a telegrapher brought him from the small town of Worthington, Indiana to Washington, D.C. His steady job as a code clerk in the Department of State enabled him to send for his hometown sweetheart, and they were married in the District of Columbia. He was employed by the State Department from 1912 until he entered the military in 1917.

The regular duty of a code clerk at Yardley's level was simply to register incoming cables from U.S. diplomatic posts overseas and distribute them to the correct pigeon-hole. Ever restless, and bored on the night shift, Yardley took notice of incoming messages in cipher and began to wonder whether the crypto systems really protected American secrets. To keep himself amused, he attempted to solve State Department cables, and quickly learned that American secrets were not safe.

Through reading and further experimentation, Yardley became proficient at cryptanalysis, though hardly an expert. Yet, when the United States entered World War I, he met with Major Ralph Van Deman, the head of Military Intelligence, and emerged as chief of MI-8, the code section.

Yardley spent the war in Washington, starting out in an office on the mezzanine of what is now Theodore Roosevelt Hall on Fort McNair. Toward the end of the war he was sent to Europe to meet with Allied cryptologists, but little came of these meetings. He emerged from the war with the rank of major.

Major Ralph Van Deman

Although the military demobilized its COMINT units after the war, the civilian side of the U.S. government began to appreciate the potentials of Communications Intelligence.

An agreement between the Acting Secretary of State and the Secretary of War in May 1919 created the Cipher Bureau. The original concept called for a $100,000 annual appropriation, with the Army providing 60 percent. However, since the Cipher Bureau concentrated on diplomatic decrypts, which were of lesser interest to the Army, the Chief of Staff cut the Army's contribution and left funding of the Bureau primarily with the State Department.

Based on his leadership during and immediately after the war, Yardley was selected as chief of this unprecedented organization. He assembled a staff and began operations - in New York City!

There were a number of sound bureaucratic reasons for locating the Cipher Bureau outside Washington, not least of which was the location in New York of several cable companies with international connections. America's first civilian intelligence agency began work in the Big Apple disguised as a company that compiled commercial codes for banks and businesses.

Yardley later claimed that the Cipher Bureau solved the systems of two dozen foreign countries. Many of the records of the organization no longer exist, so it is impossible to verify all his claims. However, it is known that he provided valuable information from Mexican communications about on the revolution south of the border.

The Cipher Bureau is best known for its work during the Washington Conference of 1921-22 and the resultant Five-Power Naval Treaty. This gathering was an attempt to limit the size of postwar navies and thus head off an international arms race.

During the conference, Yardley himself, with assistance from his staff, solved the cipher used by the Japanese representatives to this conference.

The decrypt intelligence produced by the Cipher Bureau during the Washington Conference was of mixed importance. Some was timely and revealed the Japanese government's internal discussions (and dissents) over its negotiating position for the conference. Some of the Bureau's translations were late and covered information already revealed in the press - but even these decrypts had value, since they confirmed or refuted media reports that were of unknown validity.

The Washington Treaty imposed a limit on capital ship tonnage by the major powers. Yardley's decrypts helped the U.S. negotiators encourage Japan to accept its minimum position rather than hold out for a higher tonnage level.

Yardley later claimed that the Cipher Bureau solved the systems of two dozen foreign countries. Many of the records of the organization no longer exist, so it is impossible to verify all his claims. However, it is known that he provided valuable information from Mexican communications about on the revolution south of the border.

The Cipher Bureau is best known for its work during the Washington Conference of 1921-22 and the resultant Five-Power Naval Treaty. This gathering was an attempt to limit the size of postwar navies and thus head off an international arms race.

During the conference, Yardley himself, with assistance from his staff, solved the cipher used by the Japanese representatives to this conference.

The decrypt intelligence produced by the Cipher Bureau during the Washington Conference was of mixed importance. Some was timely and revealed the Japanese government's internal discussions (and dissents) over its negotiating position for the conference. Some of the Bureau's translations were late and covered information already revealed in the press - but even these decrypts had value, since they confirmed or refuted media reports that were of unknown validity.

The Washington Treaty imposed a limit on capital ship tonnage by the major powers. Yardley's decrypts helped the U.S. negotiators encourage Japan to accept its minimum position rather than hold out for a higher tonnage level.

The election of 1928 brought Herbert Hoover to the presidency, with Henry Stimson as his Secretary of State. Stimson was one of the towering figures in foreign and defense policy in the first half of the Twentieth Century (he also later served in Franklin Roosevelt's administration as Secretary of War).

Stimson made a decision to eliminate the Cipher Bureau. The decision likely was based on budget considerations, but it has come down to us as based on the need for acting in good faith in international relations. Whatever the reason for terminating the Cipher Bureau, when he did so Stimson spoke the single most famous sentence ever uttered about codes and ciphers: "Gentlemen do not read other gentlemen's mail."

"Gentlemen do not read other gentlemen's mail"

In his history of the Cipher Bureau, Yardley charged that Stimson had axed the organization strictly for moralistic reasons. In his own autobiography, Stimson did not deny this: he noted that although he became a heavy consumer of decrypt intelligence in wartime, certain practices that might be necessary during war were unacceptable during peace.

One other important factor apart in the decision to dissolve the Cipher Bureau was the reorganization of the Army's cryptologic units. In May 1929, the Signal Corps assumed responsibility for cryptology from Military Intelligence and wished to rebuild it from the bottom up to serve military needs better. A half-hearted offer was made to Yardley to join a new cryptologic organization, but at a salary the Signal Corps expected he would refuse.

The upshot: in late 1929, employees of the Cipher Bureau were given three months' salary as severance pay, and dismissed. They had been employed using "confidential funds," therefore had no civil service status or rehire rights.

Out of work, with a family to support, and few prospects as the Great Depression worsened, Yardley decided to write his story. It appeared first in serial form in The Saturday Evening Post, then as a book, The American Black Chamber.

The American Black Chamber was filled with good stories well told, as well as frank descriptions of Yardley's successes in cryptanalysis. It was a best-seller in 1932 -- overseas as well as domestically.

While many of his former colleagues and those now engaged in military cryptanalysis were appalled at the revelations in his book, Yardley defended his publication. He claimed self-righteously that his only motive had been to alert the United States to the weakness of its own systems and to the power of cryptanalysts. What he could do, he said, people in other nations could also do.

The American Black Chamber

It has been difficult until recently to assess the contribution of the Cipher Bureau to policy. For most cases, the only account of its activities were Yardley's own. With the exception of the Washington Naval Conference, it is impossible to state unambiguously that Yardley's operation directly affected policy formation or the outcome of negotiations.

But, if it did not provide continuity in U.S. cryptologic service, the Cipher Bureau at least had the distinction of being the first national, civilian intelligence organization in peacetime. Yardley and his staff gave the U.S. government what it had never had before, and what it would soon acquire an insatiable appetite for.